Our TTTS Journey

We first heard the term TTTS at our 12 week ultrasound, when we found out we were having twins and that they were identical. We were shocked, thrilled, excited and worried. The lovely technician doing the scan told us straight away that it looked like we had a rare type of twins, referred to as MCDA (monochrionic diamniotic), and that they could sometimes come with complications. Straight away we were classified as ‘high risk’ and told we would be outsourced to the nearest metropolitan centre (which was two hours away in Newcastle, NSW) as they simply did not have the technology or expertise to cater for our twins. She briefly explained our twins could develop something called “TTTS” and told us a little bit about what it was.

This all came as a shock. We made some calls of excitement ‘yes we are having twins’ shortly followed by ‘but it’s complicated…’. None of our family or friends seemed to realise exactly what it was we were telling them. The first thing I did was get onto google to try and find out more about MCDA twins and what was TTTS? What I found at the time wasn’t overly positive, with some of the statistics saying if my twins developed TTTS there was an 80-90% fatality rate if left untreated. So early on in the pregnancy we faced the reality that having our twins was going to mean probable intervention or the high chance of losing one or both of our children. It was a lot to take in but my partner and I tried to reassure each other and stay positive. We were determined, as every parent in the same scenario would be, that we weren’t going to be one of those statistics.

Our following check-ups were at the Maternal Foetal Medicine Clinic where we would have ultrasounds and check in with a team of midwives specialising in high risk pregnancies. The term TTTS was thrown around as a warning of what could happen, but no-one would officially “diagnose” it as it was a game of “wait and see”. Even though there was a large growth discrepancy between Twin A and Twin B they were putting it down to IUGR (Intra-Uterine Growth Restriction) which also happens when twins share the one placenta.

Every two weeks we were scanned and checked for signs of TTTS until I reached 24 weeks, at which point we were told that there were danger signs as both of our twins were in distress (not receiving enough blood supply, Twin A’s heart working hard to pump blood, risk of one twin dying and coagulated blood from that twin affecting the other twin). We were told we should consider a cord occlusion (selective termination by laser procedure that cuts off the blood supply to one twin) of one twin to give the other twin a better chance of survival. They also told us that because the chance of our twins being born with disabilities was so high that we could terminate both twins at any time in the pregnancy. They told us that the prognosis for either twins survival at 24 weeks (and especially with twins that were as small and developmentally behind as ours) is so poor that many parents make the decision to terminate. This is not shamed in any way as some people cannot commit to a life with children who are severely disabled or and some parents simply cannot bear to take the risk. This was, of course, a lot of information to take in.

By this time we knew that our twins were boys and had named them Bodhi and Jarrah. I couldn’t imagine choosing to terminate one of my children. I understood that if we didn’t intervene I risked losing one or both of them in a matter of minutes, hours or days, but I could not help but hope that they would survive and continue to grow in utero a little bit longer. We were told that the cord occlusion procedure itself was risky and that if it went wrong and they had to deliver both our twins at 24 weeks and weighing under 500 grams that they would not be ‘viable’ and would not be resuscitated. I asked for statistics and information to help us make our decision but we were told ‘this condition is so rare and the procedure performed so few times that there is no data on this’. I wanted to go home and let nature take its course. The doctors advised against this and said that if I did not opt for the cord occlusion that I should be given steroid injections (to prepare them in case of their birth) and admitted to hospital, where I would be scanned daily to check the boys progress.

I took this option and was admitted to hospital, where my partner was told he could not stay with me. Knowing that our twins could die at any time inside me was a huge shock and emotionally overwhelming. My partner and I sat together in the hospital crying, wanting both of our twins to survive, but not knowing what the future held. I was then left alone in a room with four other women; crying and feeling completely lost.

Our treatment plan was to have daily ultrasounds, waiting and watching for the boys to either improve or decline. We had a few tense days and then as they seemed to be progressing steadily my partner and I relaxed, if the doctors weren’t too worried anymore then why should we be? I began to fantasise that I would make it to thirty-something weeks and all would be fine. This was in November 2014 and I started to think they might come in January the next year. After a few days on the ward I was really tired of no sleep, bad food and constant bombardment of hospital staff, so asked if I could stay in some cottages on site at the hospital. This was allowed but I still was not supposed to leave the grounds. I stuck to reading books, eating (of course!) and having family come and keep me company. They had told me I would be there until my babies came, whether it was two days or two months away…

Two weeks after my admission, at 26 weeks gestation, they saw more signs of distress during an ultrasound (Twin A’s blood supply to his brain was compromised) and urged us to deliver the twins there and then. It was then that they said “they have developed acute TTTS” which is the type of TTTS that develops quickly (minutes/hours), compared to chronic TTTS which is a slower progression over time. The boys shared arterial blood connections and their blood flow was now uneven, with more blood circulating around Twin B’s body than Twin A’s. They could see that Twin A’s blood vessels in his brain were opening as wide as they could to allow blood through, but as soon as blood was entering his body it was being shunted out too quickly and he wasn’t receiving enough blood supply. Essentially, his brain could be damaged or fail to function at any moment. I wasn’t sure what to do and looked to my partner for guidance, who was very affirmative in getting me to the operating room as quick as possible! We made quick phone calls to our mums and dads who lived two hours away and would not be able to make it in time for their birth.

It was late afternoon by this stage and they said they needed to deliver them asap as they could not guarantee whether Twin A would live from one minute to the next and they wanted to deliver them while all the specialists were on hand and hadn’t ‘clocked off’ for the day. I remember that I straight out did not want to do it. I didn’t want to believe there was anything wrong. All had been well for a while, so why was it so urgent now? I had so many unanswered questions in my head and all I could feel was uncertainty. My partner was reassuring me that we should deliver straight away if we wanted to give BOTH our boys the best chance of survival, so we prepared for an emergency caesarean. All the while I could feel my boys kicking around inside me as if there was no problem in the world.

Jarrah (Twin A, weighing 590 grams) was born first and born breathing. I heard a faint cry when he came out and was relieved. We had been previously told that if the boys did not weigh enough and were not breathing when they were born that they might not resuscitate or ‘work on them’. When I heard that cry it reassured me that everything would be done to save my children. Bodhi (Twin B, weighing 740 grams) was born less than a minute later, in his sac, without a sound. I worried as I had felt him be pulled from me and then nothing; no words from doctors and no cry. I panicked and questioned my partner, who couldn’t see or hear anything. We later found out that when they burst the sac he was born in, he inhaled some fluid and had to be ventilated straight away, hence no sound…but he was alive. Both of my miracles were alive!

They brought Jarrahs crib up next to the operating table but I could only see a pile of blankets and a little purple hand poking out from beneath a big oxygen mask, then he was whisked away. I never saw them take Bodhi out but my partner was allowed to take a photo of each boy and came to show me as I was being stitched up. They took the boys to NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) and my partner went to be with them while I was in recovery. As my two epidurals had failed (I chose to use gas for the entire procedure rather than general anaesthetic as I wanted to see and feel my boys being born) I was able to move my legs and leave recovery quickly. I was then wheeled into the NICU and saw my boys for the first time; tiny red-skinned babies with tubes and cords everywhere, but to me they were so beautiful!

I was able to hold their hands and feet and talk to them. Crying, I told them I was sorry that they had to come into this world so early and sorry for how they were born and sorry for so many things…but most importantly I told them I love you over and over again and that they were so beautiful and amazing and strong! I was overwhelmed with love…I was so proud of them and yet I also felt guilty for all the suffering they were now going through. I laid awake all night in the ward, crying for them and waiting to see them again.

Every minute of the day that I could be beside their cribs I was. I would express milk beside their cribs so I could sit and look at them, not missing a thing. Sometimes I was able to hold their hands or place my hand on their back or head to ‘confine hold’ them which preemie babies find more reassuring than stroking or patting. Some days they were too fragile to touch and we weren’t allowed into the cribs. I would read them lots of stories to make sure they heard our voices and help them feel safe. They endured so much pain and suffering and yet they continued to grow and be strong every day. We used to read the boys positive affirmations every day and tell them how big and strong they were getting, and of course how loved they were. My children inspired me, I was in awe of them. I survived on little sleep, often staying with them until midnight and then constantly worrying and calling the NICU all hours of the night to check on them. We were lucky to have secured a room at the Newcastle Ronald McDonald House, which is on site at the hospital and only a five minute walk to the NICU. I can’t tell you how many times we walked up and down to the hospital and back.

For the first few weeks of life the boys shared similar issues, mainly needing breathing support for their immature lungs. Initially they required CPAP, then a few days later they were both ventilated on and off for periods of time, then they both went back to CPAP. They both had blood transfusions and were treated ‘under the lights’ (phototherapy) for jaundice. About two weeks into our NICU journey they both died, completely out of the blue, at exactly the same time! My partner was standing at one crib and I was standing beside the other crib when all of a sudden the beeping of their monitors got louder and faster and we watched their heart rates fall. They were quickly extubated (ventilation removed), re-intubated (re-ventilated) and resuscitated in front of our eyes as we watched in horror, thinking we would lose them both, but they astonishingly came back to life! The doctors then joked that Jarrah was the ‘naughty one’ who had started it and Bodhi had followed his bad influence. Jarrah was the smaller twin and had more severe issues, which included needing two courses of steroids to reduce lung inflammation. We almost lost him numerous times. Bodhi was the bigger twin and plodded along quite content, making good progress and impressing everyone.

Personality wise Jarrah was our firey twin, always kicking and thrashing, especially when doctors were trying to perform procedures. We would call him ‘spunky monkey’ and when he went blue from not breathing we would say he was in ‘smurf mode’. He often held his breath and wouldn’t breathe when handled, so simple things like changing a nappy and taking his temperature would have to be paced and take a long time. He had a lot of fight and a lot of willpower. Bodhi was the cruisy twin; he was cool, calm and collected. He was very sweet and placid, usually happy sleeping all curled up inside his nest of blankets. He didn’t like his nappy being changed either, but he didn’t hold his breath and turn blue like Jarrah did. Bodhi enjoyed head massages when his CPAP beanie was off during his ‘cares’ (where the parents do nappy changes, take temperatures etc) and if you pushed against his little foot he always pushed back. He loved holding hands and having our hands on him. Jarrah was more sensitive to touch and so we were able to do more hands on things with Bodhi than Jarrah for the first few weeks, purely because of how fragile Jarrah was.

After 12 days I was able to hold Bodhi for the first time on a pillow which was nestled beside my chest. A few days later I got to hold Jarrah up next to my chest too. Holding my boys felt so perfect, it just felt ‘right’. They smelled amazing, looked beautiful and melted my heart. I had missed them so much.

We had milestones like this along the way, where they put on weight and were able to have more breastmilk. All the little things they do are a big deal when your children are so fragile. All seemed to be going well despite their early entrance into the world and terrifying diagnosis for their predicted quality of life. We had been prepared for the worst but had seemed to be ‘beating the odds’ so far, for which we were very grateful. We cherished every single moment with our boys and rarely left their side, except to sleep, feed ourselves and change clothes.

At almost one month old Bodhi started to show signs he was sick, but from what we couldn’t tell. He became lethargic, pale and generally ‘not himself’. We noticed the changes and asked doctors, who assured us that his pale skin and lethargy were common issues in preemie babies. A few days later a routine blood test showed dangerously high levels of potassium in his blood, pointing towards kidney failure. We worried and stressed and read everything we could find about it on the internet. The doctors started to restrict his fluids and asked kidney specialists in Sydney for their advice. Bodhi had been on diuretics to remove fluid from his lungs to help him breathe and while they didn’t think this was the problem, they were ceased as a precaution. Over the course of a few short days we saw our boy decline and become a shell of the baby he once was.

Bodhi became swollen as his body could not get rid of the excess fluid. All blood tests and ultrasounds showed there was nothing anatomically wrong with his kidneys, but still they were failing to function properly. The specialist from Sydney visited and helped make a management plan. Bodhi’s urine output, however, was almost non-existent, and staff could not accurately record it as the bags they put on to collect it would leak or they would accidentally throw samples away or record the wrong amount for the wrong period of time. It was very frustrating, worrying and stressful. I did everything I could; asked every question I could think of, asked for a wave of prayers and love and healing from our loved ones and community. The doctors assured us he could get better as I watched my sons body deteriorate and him stop moving, stop interacting, stop holding on…he was re-ventilated as his lungs were failing to keep up and his body was working very hard.

One night I felt something was not right and demanded more answers. The NUM (Nursing Unit Manager) I spoke to reaffirmed all the information they had for me and told me to go get some rest. I didn’t want to leave but my partner and mum also encouraged me to go back to Ronald McDonald house to get some sleep. After a few hours of rest I got up to express milk and had a phone call from the NICU saying to come up straight away. This was around 3.30am and I knew it wasn’t good news. When we got there Bodhi’s doctor was already there, which we knew was not a good sign. His kidneys were failing and while they were doing everything they could to save him he was declining rapidly. His body was ‘acidotic’ as his kidneys were not filtering out the toxins from his system. When a person is acidotic for too long the toxins start to affect the major organs; lungs, heart, brain…and they also start to fail.

Bodhi was still too small and fragile for dialysis or a transplant. If the medications didn’t work we were told we would be offered ‘comfort care’ where the baby is made comfortable and passes away at the parents’ digression. I sat with him, with my hands covering his body in his crib as I prayed for a miracle. I was in disbelief and wanted it to be me instead of him. I sang songs to him and hoped something would change. A few hours later Bodhi’s heart rate dropped as he went into cardiac failure. He was still in his crib at this time with the tubes and cords still attached for medications. I had my hands on him and was singing the song I would always sing to him. He was drifting away. When the doctors ran over to work on him I knew I could not watch my son die under the hands of doctors. I brought him into this world and I would be the one to take him out of it. At that point we were told he was not going to improve and it was only a matter of time before his heart gave out completely. We chose to give him comfort care, so his medications were removed and he was brought into a room with us with only his breathing support and one line for pain relief still in place.

We held him, cried, told him we loved him, spoke of many things…spoke of all the adventures he would be coming on, all the plans we had for him, how much he meant to us. We sang and cried some more. I noticed his colour changing and him fading. He would open his eyes every now and again which made me smile because he was so beautiful and cry because I was losing him, because I was the one making the choice of when to let him go. As a mother we bring our children into the world to protect them from all harm and my poor boy had suffered so much pain because of his prematurity. I felt I had failed as a mother and now all I could do was hold him and kiss him so that he felt safe and loved.

He was no longer in pain. That was what I had wanted for him the most, for the pain to stop. When he started having difficulty with his breathing tube the nurse came over to fix it and I signalled her away, I didn’t want anyone else intervening with him or ‘working on him’ now. He was going to die, let it be peaceful and not at the hands of medical intervention. I asked for his tube to be taken out and was finally able to hold my son with no attachments. I had never been able to hold him so close or so freely since he was born, and now he was going to die.

I pulled him in close and smelt him and told him I loved him. They said there were no guarantees how long he would live; minutes or hours. I asked my mother to sing and while she was singing I felt him gasp for air and take his last breath. The nurse came to check his heart rate, which was still present but slowing. She said he was gone but his body was still shutting down, she called it the ‘in-between time’. We continued to sing and after a few more songs I felt his ‘presence’ had left his body. I no longer felt he was in there. The doctor came in to confirm time of death. That was it, my boy was gone. Terrible sadness and sorrow followed. Loss of life and loss of a child is a grief I cannot explain. Grief is love with nowhere to go because that person is always missing.

It’s because of TTTS that my boys came early. It is because they were premature babies that my son Bodhi passed away. Before I had my boys TTTS was something I had never heard of and now it is something I wouldn’t wish on anyone, no parent or child. Looking back now I see that one of the hardest parts about our TTTS journey was not having the information there to learn about it and not having anyone who had been through a similar thing to talk to. I couldn’t explain it to my family and friends because I really didn’t know enough about it or what to say. How do we navigate the unknown?

Since losing Bodhi we have always been open to sharing our experience in the hope that we can help others, whether it’s through relating to our journey or just knowing someone else has been there and survived it. Many times we didn’t feel that we could, or wanted to, survive without him. We almost lost Jarrah due to respiratory failure after Bodhi died and I thought at that stage that I would be going home without either of my babies, and I’m well aware that for some families that is their reality. How hard and terrible and sad it is for all of us to be without our children. While I am grateful to have Jarrah it does not change the hurt and loss of Bodhi.

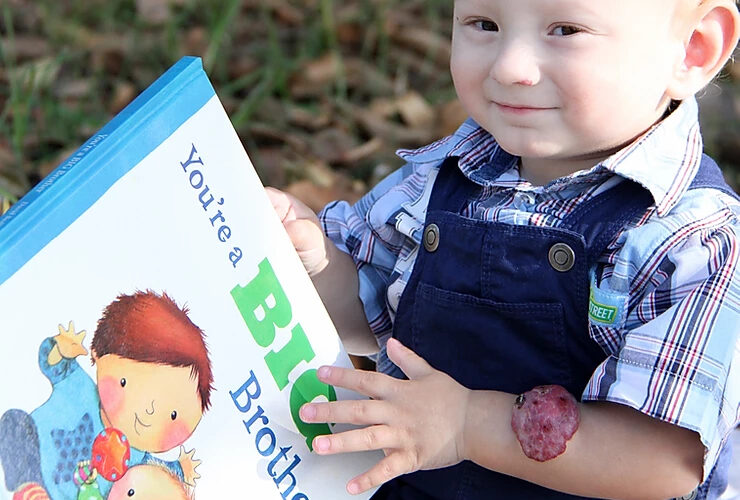

Jarrah was in the NICU for his first 4 months of life. While in NICU he had laser surgery on his eyes to save his sight as he suffered from ROP (Retinopathy of Prematurity) which is an eye condition common in preemies with low birth weight, born at early gestation and needing oxygen support. He continued to require substantial breathing support and came home on Oxygen support until his first birthday. It was during his first year at home that I linked in with other TTTS mums on Facebook who had shared similar experiences and we all expressed that we had a lack of support and information while going through our unique journeys. Thus, TTTS Australia Inc was born in the hope that we could provide families with the support that we never had. Our hearts go out to any family who is going through a TTTS journey.

Story written by Mum, Taycee-Lee Jones